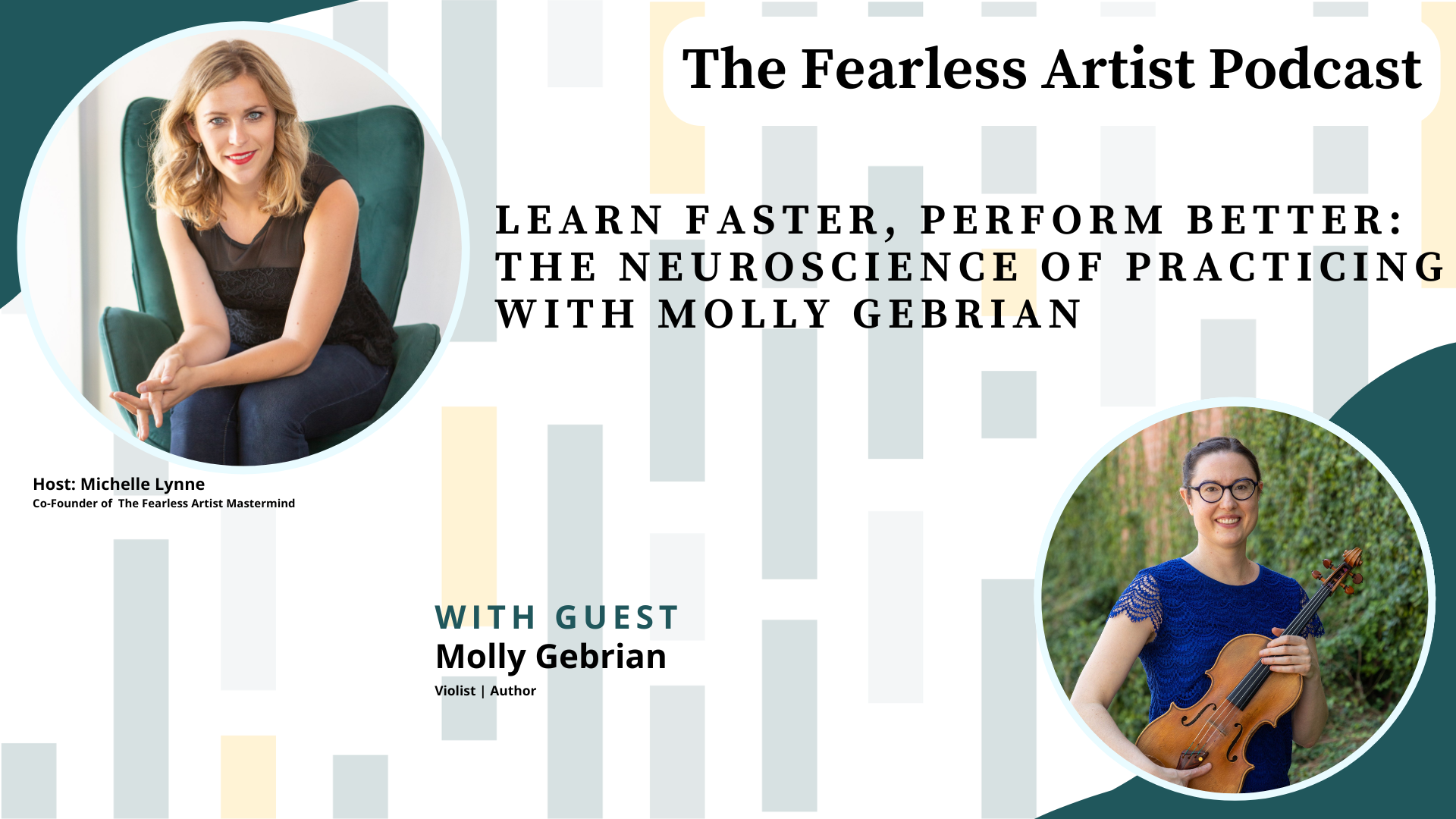

Learn Faster, Perform Better: The Neuroscience of Practicing with Molly Gebrian

Guest:

Molly Gebrian

Violist | Author

Dr. Molly Gebrian is a professional violist with a background in neuroscience. Holding degrees in both music and neuroscience from Oberlin College and Conservatory, New England Conservatory of Music, and Rice University, her area of expertise is applying the science of learning and memory to practicing and performing. Given this expertise, she is a frequent presenter on the neuroscience of practicing at conferences, universities, and music festivals in the US and abroad. Her book, Learn Faster, Perform Better: A Musician’s Guide to the Neuroscience of Practicing was released in July 2024 by Oxford University Press. As a violist, her performing is focused on promoting the music of marginalized composers, particular those from groups traditionally underrepresented in classical music. Her principal teachers include Peter Slowik, Carol Rodland, James Dunham and Garth Knox. Previously, she was the viola professor at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire and the University of Arizona. After a decade of teaching viola at the collegiate level, she joined the faculty at New England Conservatory of Music in Fall 2024 as the inaugural Teaching Artistry Scholar-in-Residence to teach about the science of practicing.

Subscribe to The Fearless Artist Podcast

Intro/Outro music by Michelle Lynne • Episode produced by phMediaStudio, LLC